Layerinitis

Layerinitis is when teams put code where they are most comfortable while optimizing for speed vs putting the code where it belongs when considering a longer term perspective on the overall software system.

Layerinitis is the virus infects growing engineering orgs the most.

As your eng org grows you have to organize into teams. Companies start with shared ownership of the code base and small project teams that form and disband. It’s a good model, but past 50+ engineers that falls apart…

* image adapted from xkcd

* image adapted from xkcd

In 2015 at Shopify there was a busy file called api_client.rb. I decided to look up the last 20 committers and talk about the reason for changes they made. Everyone was adding new attributes, but when asked why the answer was “I was just following what the previous committer did” an “had a deadline”.

The design philosophy of that entire area of Shopify was shared across everyone. But there was no real owner or steward. As they say, the fastest way to starve a horse is to ask two people to feed it.

So as you’d expect, as your org grows, you create teams that have stewardship for areas of your product. So that there’s some architectural vision and stewardship about different areas. Not to mention that many gnarly and complex areas take time to master and you need continuity in knowledge.

There’s a lot of research that shows that code ownership increases the quality of software.

Now that you’re in teams by subsystem, you think you’ve got everything figured out. You define boundaries in your software, modularity is good. You can reduce dependencies with good APIs, practice DDD, and increase the overall quality all at once. You’re winning! That was easy… right?

We modularized, albeit somewhat retroactively, at Shopify. But it increased the quality of the product and people knew who to talk with about different areas.

But what you didn’t realize is that layerinitis has been lurking just waiting to attack your org. It’s triggered right at that moment when you think you have the perfect architecture and team structure. And it hits hard.

You also likely have PMs matched up to each team and you want them to be as independent as possible. You want to stay fast and nimble and your incentives are aligned for that (promotions, raises).

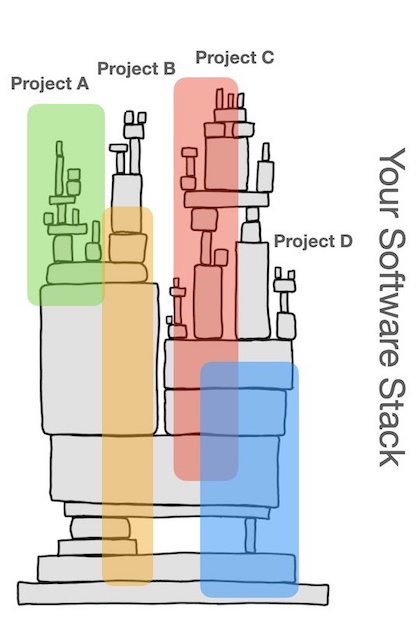

Then you realize that 80% of the projects that introduce new features or capabilities look like the diagram below. They don’t fit nicely into one layer of your stack, they cross several.

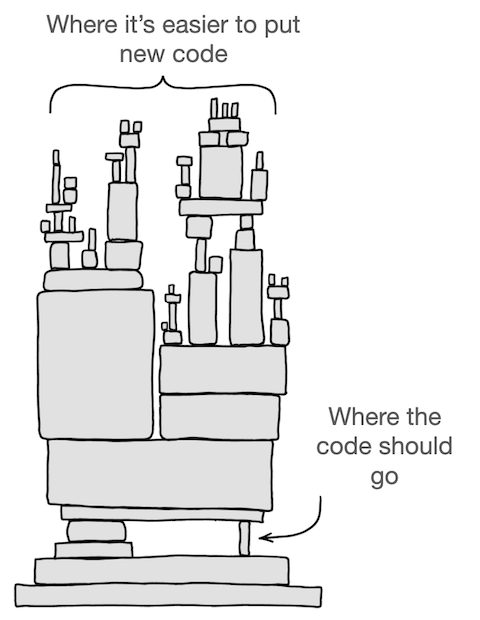

Then you noticed that new code is always added at the top of your stack. This is a very human response by teams, you have incentives aligned to ship fast at the teams level and it’s much easier to measure that vs if the code in the right spot for the long term health of your system.

The technical definition for layerinitis is teams putting code where they are most comfortable while optimizing for speed vs putting the code where it belongs when considering a longer term perspective on the overall software system.

It’s very easy to diagnose, so that’s great news. Ask teams where the code should go for their project if they break down the capabilities they are introducing with their project into the model introduced here in Chapter 2 about platform investments.

Let’s pause a second. Layerinitis isn’t bad, it’s a virus that every org will get. We’ve all been there. But there are cultural, process, and tooling tricks you can implement that will prevent layerinitis from crippling your teams.

Starting with culture, ask yourself, do teams have permission to learn and build confidence with different parts of your software stack?

One memorable experience at Shopify was when we tried to add subscriptions to the platform for 2 years. The team who owned the featured owned the UI parts of the online store. So every solution ended up a very UI focused solution.

I took the team into a boardroom, they were all extremely smart engineers. They were stressed. I changed the goals of the project: 1) your mission is to find the best place to build subscriptions into Shopify 2) build a prototype / fork any repo and we will throw it away.

A big lesson from this is that the team had the skill to do the work, but never had permission to deeply build confidence in other areas of the code base. They didn’t see their role as stewards of the overall architecture of Shopify vs shipping the feature.

We often forget that prototyping isn’t just about finding a good architecture or figuring out how long something will take to build. One of the most important benefits of prototypes is increasing the confidence in your engineering teams to work and understand layers.

I’ve seen so many teams that replace prototypes with roadmaps. Then they stop building to learn. And now they have roadmaps with no substance. It’s a vicious circle.

There’s another big side effect of using prototypes as a way to dampen layerinitis. Often the prototype team end of digging into platform / infra level areas that are often owned by small teams. Those teams really appreciate having more people learn about their areas.

Over time I’ve seen a healthy growth of morale and committers across different layers just by encouraging more cross-layer prototype at the start of large projects. And that builds more long term resiliency of knowledge across your teams.

Once you have a few good cultural habits, the next change that helps is a process one. Ensure you have enough flexibility in your roadmaps to put people from across different layers of your stack onto the projects that need them…

This may sound trivial, but every company has an army of people managing crazy gantt charts that will explode when re-jiggle people. These charts are intimidating, and more so are the people garding them with their life. But do it anyway. Because that Gantt chart is a lie anyway. If the code isn’t put in the right spot you’re not just messing up a perfect plan, but more importantly you’re not going to build what’s needed and mortgaging your future.

You had one job as a manager… put the right skills on the right projects. Period.

The next layerinitis defence is standardizing access and setup of any code base in your company. You should have the same command to setup a dev environment, test, tools for every code base.

You need amazing READMEs that assume that those reading are new and want to learn how to contribute vs just use. Again, sounds trivial but some many teams have crappy READMEs that make it hard and intimidating to setup and contribute.

That’s the short summary of why I think that layerinitis is the worst virus that will eventually infect your engineering org and the defences you can start to build now.